Multiplication

Multiplication (symbol "×") is the mathematical operation of scaling one number by another. It is one of the four basic operations in elementary arithmetic (the others being addition, subtraction and division).

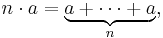

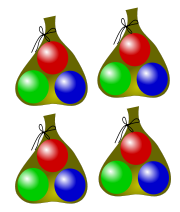

Because the result of scaling by whole numbers can be thought of as consisting of some number of copies of the original, whole-number products greater than 1 can be computed by repeated addition; for example, 3 multiplied by 4 (often said as "3 times 4") can be calculated by adding 4 copies of 3 together:

Here 3 and 4 are the "factors" and 12 is the "product".

There are differences amongst educationalists which number should normally be considered as the number of copies or whether multiplication should even be introduced as repeated addition.[1]

Multiplication of rational numbers (fractions) and real numbers is defined by systematic generalization of this basic idea.

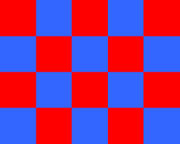

Multiplication can also be visualized as counting objects arranged in a rectangle (for whole numbers) or as finding the area of a rectangle whose sides have given lengths (for numbers generally). The area of a rectangle does not depend on which side is measured first which illustrates that the order in which numbers are multiplied together does not matter.

In general the result of multiplying two measurements gives a result of a new type depending on the measurements. For instance:

The inverse of multiplication is division: as 3 times 4 is equal to 12, so 12 divided by 3 is equal to 4.

Multiplication is generalized further to other types of numbers (such as complex numbers) and to more abstract constructs such as matrices. For these more abstract constructs, the order in which the operands are multiplied sometimes does matter.

Contents |

Notation and terminology

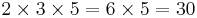

Multiplication is often written using the multiplication sign "×" between the terms; that is, in infix notation. The result is expressed with an equals sign. For example,

(verbally, "two times three equals six")

(verbally, "two times three equals six")

There are several other common notations for multiplication:

- Multiplication is sometimes denoted by either a middle dot or a period:

- The middle dot is standard in the United States, the United Kingdom, and other countries where the period is used as a decimal point. In other countries that use a comma as a decimal point, either the period or a middle dot is used for multiplication.

- The asterisk (as in

5*2) is often used in programming languages because it appears on every keyboard. This usage originated in the FORTRAN programming language.

- In algebra, multiplication involving variables is often written as a juxtaposition (e.g. xy for x times y or 5x for five times x). This notation can also be used for quantities that are surrounded by parentheses (e.g. 5(2) or (5)(2) for five times two).

- In matrix multiplication, there is actually a distinction between the cross and the dot symbols. The cross symbol generally denotes a vector multiplication, while the dot denotes a scalar multiplication. A like convention distinguishes between the cross product and the dot product of two vectors.

The numbers to be multiplied are generally called the "factors" or "multiplicands". When thinking of multiplication as repeated addition, the number to be multiplied is called the "multiplicand", while the number of multiples is called the "multiplier". In algebra, a number that is the multiplier of a variable or expression (e.g. the 3 in 3xy2) is called a coefficient.

The result of a multiplication is called a product, and is a multiple of each factor that is an integer. For example 15 is the product of 3 and 5, and is both a multiple of 3 and a multiple of 5.

Computation

The common methods for multiplying numbers using pencil and paper require a multiplication table of memorized or consulted products of small numbers (typically any two numbers from 0 to 9), however one method, the peasant multiplication algorithm, does not.

Multiplying numbers to more than a couple of decimal places by hand is tedious and error prone. Common logarithms were invented to simplify such calculations. The slide rule allowed numbers to be quickly multiplied to about three places of accuracy. Beginning in the early twentieth century, mechanical calculators, such as the Marchant, automated multiplication of up to 10 digit numbers. Modern electronic computers and calculators have greatly reduced the need for multiplication by hand.

Historical algorithms

Methods of multiplication were documented in the Egyptian, Greek, Babylonian, Indus valley, and Chinese civilizations.

The Ishango bone, dated to about 18,000 to 20,000 BC, hints at a knowledge of multiplication in the Upper Paleolithic era in Central Africa.

Egyptians

The Egyptian method of multiplication of integers and fractions, documented in the Ahmes Papyrus, was by successive additions and doubling. For instance, to find the product of 13 and 21 one had to double 21 three times, obtaining 1 × 21 = 21, 2 × 21 = 42, 4 × 21 = 84, 8 × 21 = 168. The full product could then be found by adding the appropriate terms found in the doubling sequence:

- 13 × 21 = (1 + 4 + 8) × 21 = (1 × 21) + (4 × 21) + (8 × 21) = 21 + 84 + 168 = 273.

Babylonians

The Babylonians used a sexagesimal positional number system, analogous to the modern day decimal system. Thus, Babylonian multiplication was very similar to modern decimal multiplication. Because of the relative difficulty of remembering 60 × 60 different products, Babylonian mathematicians employed multiplication tables. These tables consisted of a list of the first twenty multiples of a certain principal number n: n, 2n, ..., 20n; followed by the multiples of 10n: 30n 40n, and 50n. Then to compute any sexagesimal product, say 53n, one only needed to add 50n and 3n computed from the table.

Chinese

In the mathematical text Zhou Bi Suan Jing, dated prior to 300 B.C., and the Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, multiplication calculations were written out in words, although the early Chinese mathematicians employed Rod calculus involving place value addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. These place value decimal arithematic algorithms were introduced by Al Khwarizmi to Arab countries in the early 9th century.

Indus Valley

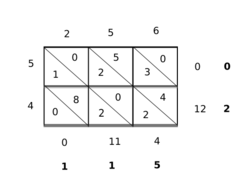

The early Indian mathematicians of the Indus Valley Civilization used a variety of intuitive tricks to perform multiplication. Most calculations were performed on small slate hand tablets, using chalk tables. One technique was that of lattice multiplication (or gelosia multiplication). Here a table was drawn up with the rows and columns labelled by the multiplicands. Each box of the table was divided diagonally into two, as a triangular lattice. The entries of the table held the partial products, written as decimal numbers. The product could then be formed by summing down the diagonals of the lattice.

Modern method

The modern method of multiplication based on the Hindu–Arabic numeral system was first described by Brahmagupta. Brahmagupta gave rules for addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Henry Burchard Fine, then professor of Mathematics at Princeton University, wrote the following:

- The Indians are the inventors not only of the positional decimal system itself, but of most of the processes involved in elementary reckoning with the system. Addition and subtraction they performed quite as they are performed nowadays; multiplication they effected in many ways, ours among them, but division they did cumbrously.[2]

Products of measurements

When two measurements are multiplied together the product is of a type depending on the types of the measurements. The general theory is given by dimensional analysis. This analysis is routinely applied in physics but has also found applications in finance. One can only meaningfully add or subtract quantities of the same type but can multiply or divide quantities of different types.

A common example is multiplying speed by time gives distance, so

- 50 kilometers per hour × 3 hours = 150 kilometers.

Products of sequences

Capital pi notation

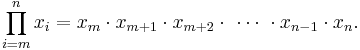

The product of a sequence of terms can be written with the product symbol, which derives from the capital letter Π (Pi) in the Greek alphabet. Unicode position U+220F (∏) contains a glyph for denoting such a product, distinct from U+03A0 (Π), the letter. The meaning of this notation is given by:

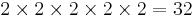

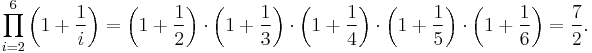

The subscript gives the symbol for a dummy variable (i in this case), called the "index of multiplication" together with its lower bound (m), whereas the superscript (here n) gives its upper bound. The lower and upper bound are expressions denoting integers. The factors of the product are obtained by taking the expression following the product operator, with successive integer values substituted for the index of multiplication, starting from the lower bound and incremented by 1 up to and including the upper bound. So, for example:

In case m = n, the value of the product is the same as that of the single factor xm. If m > n, the product is the empty product, with the value 1.

Infinite products

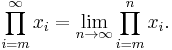

One may also consider products of infinitely many terms; these are called infinite products. Notationally, we would replace n above by the lemniscate ∞. The product of such a series is defined as the limit of the product of the first n terms, as n grows without bound. That is, by definition,

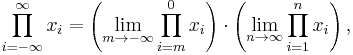

One can similarly replace m with negative infinity, and define:

provided both limits exist.

Properties

For the natural numbers, integers, fractions, and real and complex numbers, multiplication has certain properties:

- Commutative property

- The order in which two numbers are multiplied does not matter:

.

.

- Associative property

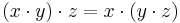

- Expressions solely involving multiplication are invariant with respect to order of operations:

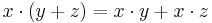

- Distributive property

- Holds with respect to addition over multiplication. This identity is of prime importance in simplifying algebraic expressions:

- Identity element

- The multiplicative identity is 1; anything multiplied by one is itself. This is known as the identity property:

- Zero element

- Anything multiplied by zero is zero. This is known as the zero property of multiplication:

- Zero is sometimes not included amongst the natural numbers.

There are a number of further properties of multiplication not satisfied by all types of numbers.

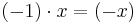

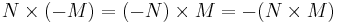

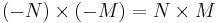

- Negation

- Negative one times any number is equal to the opposite of that number.

- Negative one times negative one is positive one.

- The natural numbers do not include negative numbers.

- Inverse element

- Every number x, except zero, has a multiplicative inverse,

, such that

, such that  .

. - The natural numbers and integers do not have inverses.

- Order preservation

- Multiplication by a positive number preserves order: if a > 0, then if b > c then ab > ac. Multiplication by a negative number reverses order: if a < 0 and b > c then ab < ac.

- The complex numbers do not have an order predicate.

Other mathematical systems that include a multiplication operation may not have all these properties. For example, multiplication is not, in general, commutative for matrices and quaternions.

Axioms

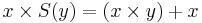

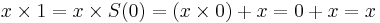

In the book Arithmetices principia, nova methodo exposita, Giuseppe Peano proposed axioms for arithmetic based on his axioms for natural numbers.[3] Peano arithmetic has two axioms for multiplication:

Here S(y) represents the successor of y, or the natural number which follows y. The various properties like associativity can be proved from these and the other axioms of Peano arithmetic including induction. For instance S(0). denoted by 1, is a multiplicative identity because

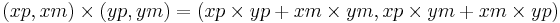

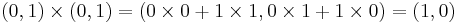

The axioms for integers typically define them as equivalence classes of ordered pairs of natural numbers. The model is based on treating (x,y) as equivalent to x−y when x and y are treated as integers. Thus both (0,1) and (1,2) are equivalent to −1. The multiplication axiom for integers defined this way is

The rule that −1×−1 = 1 can then be deduced from

Multiplication is extended in a similar way to rational numbers and then to real numbers.

Multiplication with set theory

It is possible, though difficult, to create a recursive definition of multiplication with set theory. Such a system usually relies on the Peano definition of multiplication.

Cartesian product

The definition of multiplication as repeated addition provides a way to arrive at a set-theoretic interpretation of multiplication of cardinal numbers. In the expression

if the n copies of a are to be combined in disjoint union then clearly they must be made disjoint; an obvious way to do this is to use either a or n as the indexing set for the other. Then, the members of  are exactly those of the Cartesian product

are exactly those of the Cartesian product  . The properties of the multiplicative operation as applying to natural numbers then follow trivially from the corresponding properties of the Cartesian product.

. The properties of the multiplicative operation as applying to natural numbers then follow trivially from the corresponding properties of the Cartesian product.

Multiplication in group theory

There are many sets that, under the operation of multiplication, satisfy the axioms that define group structure. These axioms are closure, associativity, and the inclusion of an identity element and inverses.

A simple example is the set of non-zero rational numbers. Here we have identity 1, as opposed to groups under addition where the identity is typically 0. Note that with the rationals, we must exclude zero because, under multiplication, it does not have an inverse: there is no rational number that can be multiplied by zero to result in 1. In this example we have an abelian group, but that is not always the case.

To see this, look at the set of invertible square matrices of a given dimension, over a given field. Now it is straightforward to verify closure, associativity, and inclusion of identity (the identity matrix) and inverses. However, matrix multiplication is not commutative, therefore this group is nonabelian.

Another fact of note is that the integers under multiplication is not a group, even if we exclude zero. This is easily seen by the nonexistence of an inverse for all elements other than 1 and -1.

Multiplication in group theory is typically notated either by a dot, or by juxtaposition (the omission of an operation symbol between elements). So multiplying element a by element b could be notated a  b or ab. When referring to a group via the indication of the set and operation, the dot is used, e.g. our first example could be indicated by

b or ab. When referring to a group via the indication of the set and operation, the dot is used, e.g. our first example could be indicated by

Multiplication of different kinds of numbers

Numbers can count (3 apples), order (the 3rd apple), or measure (3.5 feet high); as the history of mathematics has progressed from counting on our fingers to modelling quantum mechanics, multiplication has been generalized to more complicated and abstract types of numbers, and to things that are not numbers (such as matrices) or do not look much like numbers (such as quaternions).

- Integers

is the sum of M copies of N when N and M are positive whole numbers. This gives the number of things in an array N wide and M high. Generalization to negative numbers can be done by

is the sum of M copies of N when N and M are positive whole numbers. This gives the number of things in an array N wide and M high. Generalization to negative numbers can be done by  and

and  . The same sign rules apply to rational and real numbers.

. The same sign rules apply to rational and real numbers.

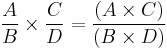

- Rational numbers

- Generalization to fractions

is by multiplying the numerators and denominators respectively:

is by multiplying the numerators and denominators respectively:  . This gives the area of a rectangle

. This gives the area of a rectangle  high and

high and  wide, and is the same as the number of things in an array when the rational numbers happen to be whole numbers.

wide, and is the same as the number of things in an array when the rational numbers happen to be whole numbers.

- Real numbers

is the limit of the products of the corresponding terms in certain sequences of rationals that converge to x and y, respectively, and is significant in calculus. This gives the area of a rectangle x high and y wide. See Products of sequences, above.

is the limit of the products of the corresponding terms in certain sequences of rationals that converge to x and y, respectively, and is significant in calculus. This gives the area of a rectangle x high and y wide. See Products of sequences, above.

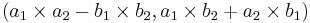

- Complex numbers

- Considering complex numbers

and

and  as ordered pairs of real numbers

as ordered pairs of real numbers  and

and  , the product

, the product  is

is  . This is the same as for reals,

. This is the same as for reals,  , when the imaginary parts

, when the imaginary parts  and

and  are zero.

are zero.

- Further generalizations

- See Multiplication in group theory, above, and Multiplicative Group, which for example includes matrix multiplication. A very general, and abstract, concept of multiplication is as the "multiplicatively denoted" (second) binary operation in a ring. An example of a ring which is not any of the above number systems is a polynomial ring (you can add and multiply polynomials, but polynomials are not numbers in any usual sense.)

- Division

- Often division,

, is the same as multiplication by an inverse,

, is the same as multiplication by an inverse,  . Multiplication for some types of "numbers" may have corresponding division, without inverses; in an integral domain x may have no inverse "

. Multiplication for some types of "numbers" may have corresponding division, without inverses; in an integral domain x may have no inverse " " but

" but  may be defined. In a division ring there are inverses but they are not commutative (since

may be defined. In a division ring there are inverses but they are not commutative (since  is not the same as

is not the same as  ,

,  may be ambiguous).

may be ambiguous).

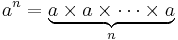

Exponentiation

When multiplication is repeated, the resulting operation is known as exponentiation. For instance, the product 2×2×2 of three factors of two is "two raised to the third power", and is denoted by 23, a two with a superscript three. In this example, the number two is the base, and three is the exponent. In general, the exponent (or superscript) indicates how many times to multiply base by itself, so that the expression

indicates that the base a to be multiplied by itself n times.

See also

- Dimensional analysis

- Multiplicative inverse, the reciprocal

- Multiplication algorithm

- Karatsuba algorithm, method for large numbers

- Toom-Cook algorithm, method for very large numbers

- Schönhage–Strassen algorithm, method for huge numbers

- Multiplication table (times table)

- Multiplication ALU, how computers multiply

- Booth's multiplication algorithm

- Floating point

- Fused multiply-add

- Multiply-accumulate

- Wallace tree

- Factorial

- Napier's bones

- Genaille-Lucas rulers

- Peasant multiplication

- Product (mathematics) - lists generalizations

- Slide rule

Notes

- ↑ Makoto Yoshida (2009). "Is Multiplication Just Repeated Addition?". http://www.globaledresources.com/resources/assets/042309_Multiplication_v2.pdf.

- ↑ Henry B. Fine. The Number System of Algebra – Treated Theoretically and Historically, (2nd edition, with corrections, 1907), page 90, http://www.archive.org/download/numbersystemofal00fineuoft/numbersystemofal00fineuoft.pdf

- ↑ PlanetMath: Peano arithmetic

References

- Boyer, Carl B. (revised by Merzbach, Uta C.) (1991). History of Mathematics. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

External links

- Multiplication and Arithmetic Operations In Various Number Systems at cut-the-knot

- Modern Chinese Multiplication Techniques on an Abacus

|

|||||